Xarray 2: DataArrays

Contents

Xarray 2: DataArrays¶

Overview¶

Why not use a Pandas DataFrame for gridded data?

Anatomy of a DataArray created from a gridded NetCDF data file

Prerequisites¶

Concepts |

Importance |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

Python basics |

Necessary |

|

Numpy basics |

Necessary |

|

Pandas |

Necessary |

|

Xarray 1 Intro |

Necessary |

Time to learn: 15 minutes

Imports¶

import xarray as xr

import pandas as pd

Why not use a Pandas DataFrame for gridded data?¶

Here is a Pandas DataFrame representation of the 500 hPa geopotential height for 0000 UTC 30 October 2012, from the ERA-5 reanalysis:

df = pd.read_csv('/spare11/atm533/data/2012103000_z500_era5.csv',index_col='latitude')

df

| 0.0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1.0 | 1.25 | 1.5 | 1.75 | 2.0 | 2.25 | ... | 357.5 | 357.75 | 358.0 | 358.25 | 358.5 | 358.75 | 359.0 | 359.25 | 359.5 | 359.75 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| latitude | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 90.00 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | ... | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 | 51072.215 |

| 89.75 | 51049.582 | 51049.582 | 51049.746 | 51049.746 | 51050.074 | 51050.074 | 51050.240 | 51050.240 | 51050.566 | 51050.566 | ... | 51048.270 | 51048.270 | 51048.598 | 51048.598 | 51048.760 | 51048.760 | 51049.090 | 51049.090 | 51049.254 | 51049.254 |

| 89.50 | 51026.950 | 51027.277 | 51027.440 | 51027.770 | 51028.098 | 51028.260 | 51028.590 | 51028.754 | 51029.082 | 51029.246 | ... | 51024.816 | 51024.980 | 51025.310 | 51025.473 | 51025.800 | 51025.965 | 51026.293 | 51026.293 | 51026.457 | 51026.785 |

| 89.25 | 51007.270 | 51007.598 | 51008.090 | 51008.254 | 51008.582 | 51009.074 | 51009.240 | 51009.566 | 51009.730 | 51010.223 | ... | 51004.320 | 51004.484 | 51004.810 | 51005.300 | 51005.465 | 51005.793 | 51005.957 | 51006.285 | 51006.777 | 51006.940 |

| 89.00 | 50990.050 | 50990.543 | 50990.707 | 50991.200 | 50991.527 | 50992.020 | 50992.348 | 50992.840 | 50993.004 | 50993.496 | ... | 50986.770 | 50987.098 | 50987.260 | 50987.754 | 50988.082 | 50988.246 | 50988.740 | 50989.066 | 50989.560 | 50989.723 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| -89.00 | 48821.510 | 48821.840 | 48822.332 | 48822.496 | 48822.990 | 48823.316 | 48823.480 | 48823.973 | 48824.300 | 48824.465 | ... | 48817.740 | 48818.230 | 48818.560 | 48819.050 | 48819.215 | 48819.707 | 48820.035 | 48820.527 | 48820.690 | 48821.348 |

| -89.25 | 48783.465 | 48783.793 | 48783.957 | 48784.450 | 48784.777 | 48784.940 | 48785.270 | 48785.598 | 48785.758 | 48786.086 | ... | 48780.840 | 48781.004 | 48781.332 | 48781.496 | 48781.990 | 48782.316 | 48782.480 | 48782.810 | 48782.973 | 48783.300 |

| -89.50 | 48745.582 | 48745.582 | 48745.746 | 48746.074 | 48746.074 | 48746.240 | 48746.240 | 48746.562 | 48746.727 | 48746.727 | ... | 48743.777 | 48743.940 | 48744.270 | 48744.270 | 48744.598 | 48744.760 | 48744.760 | 48745.090 | 48745.090 | 48745.254 |

| -89.75 | 48709.500 | 48709.500 | 48709.500 | 48709.500 | 48709.830 | 48709.830 | 48709.830 | 48709.992 | 48709.992 | 48709.992 | ... | 48708.844 | 48708.844 | 48708.844 | 48708.844 | 48709.008 | 48709.008 | 48709.008 | 48709.336 | 48709.336 | 48709.336 |

| -90.00 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | ... | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 | 48673.258 |

721 rows × 1440 columns

df.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

Index: 721 entries, 90.0 to -90.0

Columns: 1440 entries, 0.0 to 359.75

dtypes: float64(1440)

memory usage: 7.9 MB

Output the geopotential height at the grid point closest to Albany (42.75N, -73.75 W; note we have expressed the longitude as if it were degrees East)

df.loc[[42.75],['286.25']]

| 286.25 | |

|---|---|

| latitude | |

| 42.75 | 53853.285 |

While Pandas is great for many purposes, extending its inherently 2-d data representation to a multidimensional dataset, such as 4-dimensional (time, vertical level, longitude (x) and latitude (y)) gridded numerical weather prediction (NWP) or c limate model output, is unwise.

Gridded datasets and Xarray¶

The Xarray package is ideally-suited for gridded data, in particular NetCDF. It builds and extends on the multi-dimensional data structure in NumPy. We will see that some of the same methods we’ve used for Pandas have analogues in Xarray.

Anatomy of a DataArray¶

Let’s look at the same 500 hPa geopotential height field, but this time we’ll use Xarray to open the NetCDF representation.

da = xr.open_dataarray('/spare11/atm533/data/2012103000_z500_era5.nc')

First, let’s compare the size of gridded field as represented in a plain-text CSV file and in NetCDF.

! ls -lh /spare11/atm533/data/2012103000_z500_era5.csv

! ls -lh /spare11/atm533/data/2012103000_z500_era5.nc

-rw-r--r-- 1 ktyle faculty 9.5M Sep 29 2020 /spare11/atm533/data/2012103000_z500_era5.csv

-rw-r--r-- 1 ktyle faculty 2.0M Sep 29 2020 /spare11/atm533/data/2012103000_z500_era5.nc

The NetCDF-formatted file is smaller. While this particular grid is less than 10 MB either way, the space savings become significant as you scale up!

As did Pandas with its Series and DataFrame core data structures, Xarray also has two “workhorses”: the DataArray and the Dataset. Just as a Pandas DataFrame consists of multiple Series, an Xarray Dataset is made up of DataArray objects. Let’s first look at our DataArray.

# Similar to a Pandas DataFrame, we get a nice (and even more interactive) HTML representation of the object.

da

<xarray.DataArray 'z' (time: 1, latitude: 721, longitude: 1440)>

[1038240 values with dtype=float32]

Coordinates:

* longitude (longitude) float32 0.0 0.25 0.5 0.75 ... 359.0 359.2 359.5 359.8

* latitude (latitude) float32 90.0 89.75 89.5 89.25 ... -89.5 -89.75 -90.0

* time (time) datetime64[ns] 2012-10-30

Attributes:

units: m**2 s**-2

long_name: Geopotential

standard_name: geopotentialThe DataArray has the following properties:¶

It is a named data variable: ‘z’

It has three named dimensions, in order: time, latitude, and longitude.

It has three coordinate variables, corresponding to the dimensions.

It has attributes which are the data variable’s metadata.

Its coordinate variables may have their own metadata as well.

Let’s examine each of these five properties.¶

1. The data variable, z in this case, is represented by the DataArray object itself. We can query various properties of it, with methods similar to Pandas.¶

# Akin to column and row indices in Pandas:

da.indexes

Indexes:

longitude Index([ 0.0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2.0,

2.25,

...

357.5, 357.75, 358.0, 358.25, 358.5, 358.75, 359.0, 359.25, 359.5,

359.75],

dtype='float32', name='longitude', length=1440)

latitude Index([ 90.0, 89.75, 89.5, 89.25, 89.0, 88.75, 88.5, 88.25, 88.0,

87.75,

...

-87.75, -88.0, -88.25, -88.5, -88.75, -89.0, -89.25, -89.5, -89.75,

-90.0],

dtype='float32', name='latitude', length=721)

time DatetimeIndex(['2012-10-30'], dtype='datetime64[ns]', name='time', freq=None)

da.mean()

<xarray.DataArray 'z' ()> array(54036.84, dtype=float32)

da.max()

<xarray.DataArray 'z' ()> array(57970.76953125)

da.min()

<xarray.DataArray 'z' ()> array(47223.51953125)

This invocation will return the lat, lon, and time of the maximum value in the DataArray (source: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/40179593/how-to-get-the-coordinates-of-the-maximum-in-xarray)¶

da.where(da==da.max(), drop=True).coords

Coordinates:

* longitude (longitude) float32 308.5

* latitude (latitude) float32 -21.5

* time (time) datetime64[ns] 2012-10-30

# We can use loc to select via dimension values, but note that order of indices must follow dimension order.

da.loc['2012-10-30 00:00',42.75,286.25]

<xarray.DataArray 'z' ()>

array(53853.285, dtype=float32)

Coordinates:

longitude float32 286.2

latitude float32 42.75

time datetime64[ns] 2012-10-30

Attributes:

units: m**2 s**-2

long_name: Geopotential

standard_name: geopotentialWe can alternatively use Xarray’s sel indexing technique, where we specify the names of the dimension and the values we are selecting … can be in any order.

da.sel(latitude=42.75, longitude = 286.25)

<xarray.DataArray 'z' (time: 1)>

array([53853.285], dtype=float32)

Coordinates:

longitude float32 286.2

latitude float32 42.75

* time (time) datetime64[ns] 2012-10-30

Attributes:

units: m**2 s**-2

long_name: Geopotential

standard_name: geopotential2. Dimension names¶

In Xarray, dimensions can be thought of as extensions of Pandas’ 2-d row/column indices (aka axes). We can assign names, or labels, to Pandas indexes; in Xarray, these labeled axes are a necessary (and excellent) feature.

da.dims

('time', 'latitude', 'longitude')

3. Coordinates¶

Coordinate variables in Xarray are 1-dimensional arrays that correspond to the Data variable’s dimensions.

In this case, z has dimension coordinates of longitude, latitude, and time; each of these three dimension coordinates consist of an array of values, plus metadata.

da.coords

Coordinates:

* longitude (longitude) float32 0.0 0.25 0.5 0.75 ... 359.0 359.2 359.5 359.8

* latitude (latitude) float32 90.0 89.75 89.5 89.25 ... -89.5 -89.75 -90.0

* time (time) datetime64[ns] 2012-10-30

We can assign an object to each coordinate dimension.

lons = da.longitude

lats = da.latitude

times = da.time

lons

<xarray.DataArray 'longitude' (longitude: 1440)>

array([0.0000e+00, 2.5000e-01, 5.0000e-01, ..., 3.5925e+02, 3.5950e+02,

3.5975e+02], dtype=float32)

Coordinates:

* longitude (longitude) float32 0.0 0.25 0.5 0.75 ... 359.0 359.2 359.5 359.8

Attributes:

units: degrees_east

long_name: longitude4. The data variables will typically have attributes (metadata) attached to them.¶

da.attrs

{'units': 'm**2 s**-2',

'long_name': 'Geopotential',

'standard_name': 'geopotential'}

da.units

'm**2 s**-2'

5. The coordinate variables will likely have metadata as well.¶

times.attrs

{'long_name': 'time'}

lats.attrs

{'units': 'degrees_north', 'long_name': 'latitude'}

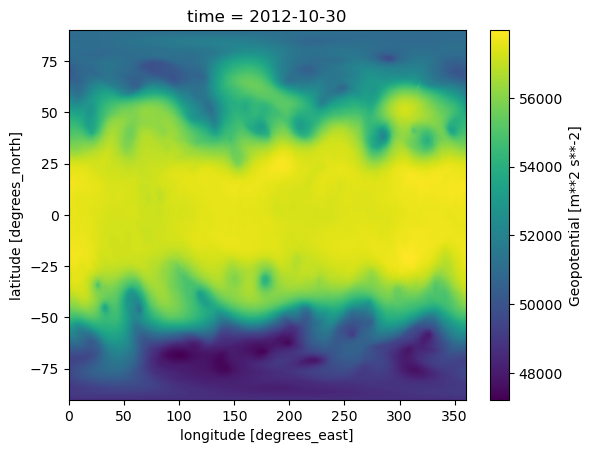

Just as with Pandas, Xarray has a built-in hook to Matplotlib so we can take a quick look at our data.¶

da.plot()

<matplotlib.collections.QuadMesh at 0x14dc3c551810>

This NetCDF file that we read in had just a single data variable … one time, at one vertical level. Typically, gridded model or reanalysis data in NetCDF format will consist of multiple variables … i.e., multiple Xarray DataArrays … known as a Dataset. In the rest of our Xarray notebooks, we will read in, analyze, and visualize examples of Datasets.¶

Summary¶

Xarray builds upon the data models provided by NumPy and Pandas.

Xarray provides read and write methods for a variety of gridded datasets, such as NetCDF, GRIB, and Zarr.

Xarray

Datasetsconsist of one or more `DataArrays’.A

DataArraytypically contains one data variable, with labeled dimensions and coordinates.

What’s Next?¶

In the next notebook, we’ll work with an Xarray Dataset and make some plots from it.